“I’m absolutely stronger. It’s measurable—I can look at my PRs and take that knowledge to the bike,” he said.

Cycling is all about suffering. It’s about finding your limits then pushing past them. But even that struggle can feel liberating.

“For me, handcycling for the first time as an adult felt so freeing,” said professional cyclist Travis Gaertner.

That freedom is especially important for the 42-year-old athlete, who also juggles his day job as a corporate consultant with being a husband and father of three. Gaertner started his pro sports career as a wheelchair basketball athlete representing Canada. His team won gold medals in 2000 and 2004, before he decided to retire from basketball to focus on his family and career.

In 2018, he picked up handcycling just for fun, as a way to maintain his fitness on the weekends.

“After a while, that competitive bug came back again,” he said.

Gaertner leveraged that ambitious appetite and went to work. He applied his knowledge of training and hired a strength coach and a cycling coach just to see how far he could go. That training soon paid off. He earned a spot on the podium in a few domestic races, made it onto the U.S. team, and began competing internationally.

Just two years later in 2020, Gaertner narrowly missed the opportunity to compete in the Tokyo Games by just 17 seconds. Now, he’s set his sights on chasing the 2024 Paris Games.

A New Training Approach

Compared to a team sport like basketball, handcycling allows Gaertner to have a better work-life balance while still competing at an elite level. “I’m much more in control of when I do my training, how I do my training, where I do my training,” he said, “and I’m still there for my family.” But he did need to make some adjustments.

In addition to gaining endurance via hours-long aerobic rides, Gaertner needed to develop strength and anaerobic power to hold pace with competitors in a race or launch an attack off the front of the field. He also wanted to build a strong core for maneuvering around tight turns on the bike with speed and control.

But strength training in a traditional gym isn’t easy for a wheelchair athlete.

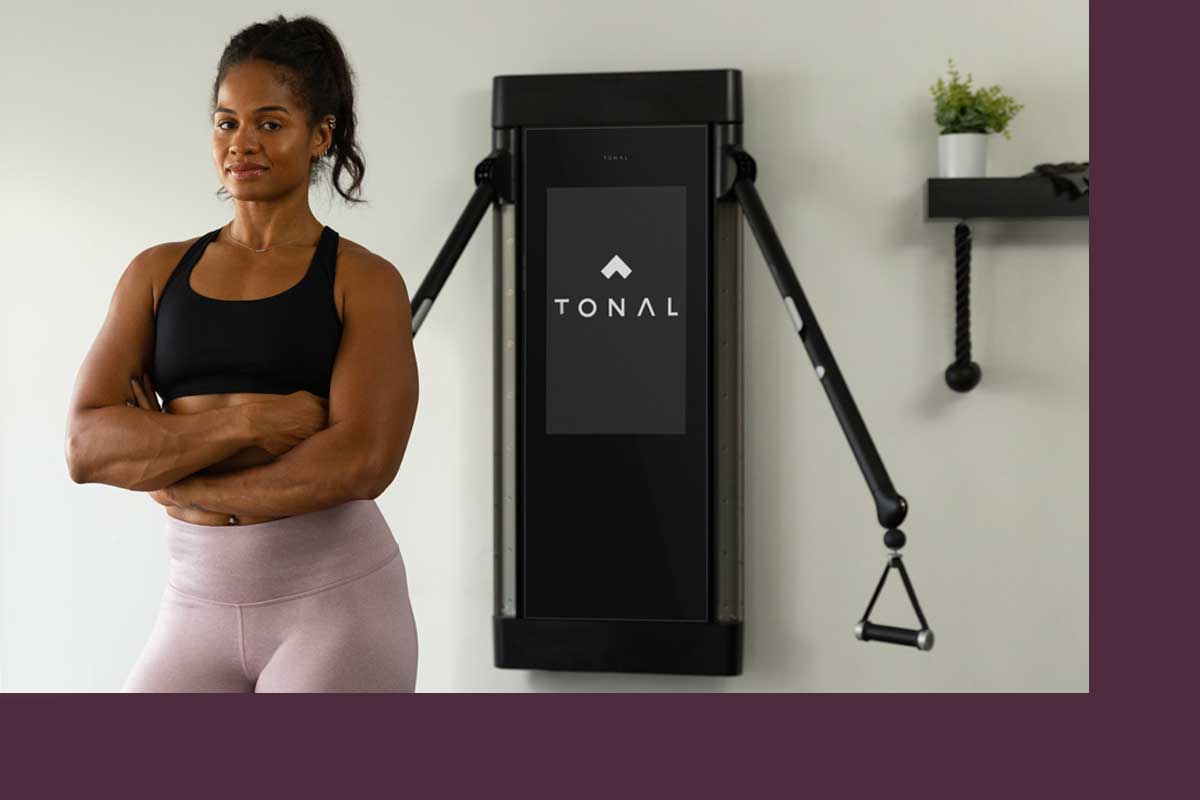

“Tonal has been revolutionary in my training. It’s one of the few products I’ve tried that actually lives up to all its promises—and even surpasses them.”

— Travis Gaertner

“I wasn’t able to perform all the exercises I knew I needed to do to get stronger on the bike,” says Gaertner. “If I go to the gym and try to lift very heavy in any given exercise, I can get into trouble if I don’t have someone to spot me. I don’t have the same ability to get on and off a bench.” Core exercises on a cable machine were challenging, too, because Gaertner had trouble getting into position to lift a weighted cable in his chair.

Then, Gaertner heard about Tonal from a friend. It sounded like the perfect fit for his needs, the flexibility he required, and what he was trying to achieve in his cycling career. “I ordered one right away and started seeing the benefits from day one,” he said. “Tonal has been revolutionary in my training. It’s one of the few products I’ve tried that actually lives up to all its promises—and even surpasses them.”

Since starting to work out on Tonal, Gaertner’s power output on the bike has increased by 10 to 15 percent. “I didn’t want my competitors to know about it,” he laughed. “It changed the way I trained so fast, and I started to see new results [so] quickly that I actually thought of it as a competitive advantage.” He was right—many of his competitors now train on Tonal as well.

On Tonal, Gaertner can challenge himself with heavier weights and trust that Spotter Mode is there to take the weight off so he doesn’t risk injuring himself. With core exercises, he can now get into position first before turning the weight on with the click of a button. “That was a game-changer,” he said. Building his core strength has helped Gaertner “tremendously” on the bike. “I can turn faster and I’m much more stable overall in the handcycle, which means I’m a lot faster.”

With the ability to increase resistance by one-pound increments, Tonal prevents Gaertner from hitting plateaus. “At the gym, I had to increase by 5 or 10 pounds,” he said. “For certain exercises, I wasn’t always ready for that jump. Tonal keeps me engaged because I always want to try and push more—even if it’s just one more pound.”

The ease of working out at home on Tonal has also helped Gaertner “say yes” to his workouts and free up time for his family and career—a feeling that’s relatable even if you’re not a world-class athlete.

Finding Strength in the Suffering

One of the main challenges of handcycling is continuing to generate power and give your max effort even when your mind and body are screaming at you to stop. With Tonal’s power meter, Gaertner can see if his power starts to dip during a set, then adjust his effort to maintain a high output.

The real-time feedback shows Gaertner if he’s losing power. “I could watch for those dips to say, every rep, I want that to be a good rep ,” he said.

Now when Gaertner feels himself start to fade on the bike, he said, “I’ve trained myself to know I can push through that. That’s when the mental aspect kicks in. When I feel like I have nothing left, I know I can keep giving that effort because I’ve experienced it before in my training.”

Every day, Gaertner knows he is getting stronger. “It’s measurable—I can look at my PRs and take that knowledge to the bike,” he said. Just as he’s hitting new PRs on Tonal, he’s seeing bigger wattage outputs on his bike’s power meter and becoming a more competitive racer.

“When I feel like I have nothing left, I know I can keep giving that effort because I’ve experienced it before in my training.”

— Travis Gaertner

For Gaertner, not making the 2020 Tokyo Games was devastating. “I felt like I let down all the people that supported me over the years, my family, and my sponsors,” he said. He even briefly considered quitting the sport. But once he realized he still loved cycling, pushing himself to his limits, and competing, he thought, “Why would I not keep going?”

Even though it’s been 20 years since his last Paralympics, Gaertner isn’t giving up on his goal. With Tonal in his corner, he’s continuing to become a stronger athlete and striving to perform better each day.

“I’ve always got new things to learn,” he said. “That’s why I’m going to continue on this journey until I’ve hit a point where I feel like I’ve got nothing else to learn, nothing else to give to the sport. I’ve still got more to give. Every year, I’m reinventing myself. I’m finding ways to improve. When that stops, I’ll stop.”